We have all marveled at the gracefulness of a cat leaping in the air, the swift movements of a hummingbird’s wings, the determined salmon swimming up river, the incredible precision of the marching feet of a millipede and the power of a galloping horse. Animals exhibit all types of movement- they walk, run, creep, hop, jump, fly, glide, paddle, and swim. By studying nature and observing animal movement scientists can better understand biomechanics, physiology, evolution, physics, and engineering.

When we think about the study of animal locomotion, the late 19th century photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion series comes to mind. His signature photographic series of the galloping horse commissioned by Leland Stanford is the most well-known, but he captured the movement of many more animals which you can find published in Animal Locomotion. An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Movements. 1872-1885 (Philadelphia, Photogravure Company of New York, 1887). In commemoration of Muybridge’s birthday on April 9th, the Library has uploaded a selection of Muybridge’s images from the Library of Congress collection into Flickr.

Many suggest that the first study of animal locomotion began in antiquity with Aristotle of Stagira (384- 322 B.C.), though I would argue that Paleolithic cave paintings, such as those found in Lascaux, exhibit the beginning of our fascination on how animals move. Aristotle’s De Animalbus (De historia animalium/History of Animals, De partibus animalium/Parts of Animals, De generatione animalium/ Generation of Animals) and his De motu animalium/ Movement of Animals discuss theories of voluntary animal motion, contending that motion originates from the heart.

The Greek physician Galen of Pergamum (A.D 129-216) did not agree with Aristotle’s theory. He argued that motion came from the brain, which acts like an engine that moves the nerves and muscles into motion. See Galen’s On the Doctrines of Plato and Hippocrates translated by Phillip de Lacy (Berlin, Akademie-Verlag, 1978-c1984) and On the Natural Faculties translated by Arthur John Brock (London, W. Heinemann; New York, D. Appleton and Company, 1916).

Scientists and thinkers during the Middle Ages focused their attention on re-examining Aristotle’s treatise on animals with new translations and commentaries. To get an idea of the tone and tenor of medieval animal locomotion theories, see Albertus Magnus’ (119?- 1280) On Animals : a Medieval Summa Zoologica translated by Kenneth F. Kitchell, Jr. & Irven Michael Resnick (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999) and On the movement and progression of animals- Aristotle and Michael of Ephesus translated by Anthony Preus (Hildesheim ; New York , Olms, 1981).

Also worth mentioning is the work of the great visionary Leonardo Da Vinci (1452- 1519) who bridged science and art with his study of animals in motion, most notably the Codex on the Flight of Birds(1505-1506).

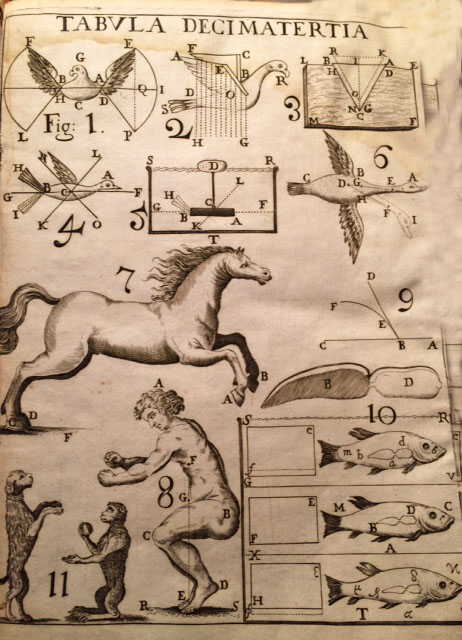

Another significant contribution to the study of animal locomotion can be found in De Motu Animalium by Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (1608-1679), who is often credited as the father of biomechanics. He studied the movement of living animals and showed that movement of the body is similar to a machine and operates by mechanical laws. For an English translation of Borelli’s seminal work De Motu Animalium (1680-81) see On the Movement of Animals translated by Paul Maquet (Berlin, New York, Springer-Verlag, c1989).

French physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904), who was a contemporary of Muybridge, is another scientist who studied animal locomotion. Marey and Muybridge both used the camera as a scientific instrument to study animal locomotion and are credited as the pioneers of ‘instantaneous’ photography and chronophotography (multiple exposures on a single plate). Marey’s work on Animal Mechanism: A Treatise on Terrestrial and Aerial Locomotion (NewYork, 1874) /La Machine Animale, Locomotion Terrestre et Aérienne (Paris, 1873) and Movement (New York, 1895)/ Le Mouvement (Paris, 1894) presented new ways to investigate animal locomotion. His research was influential. In fact, the Wright Brothers used Marey’s study on the flight of birds to help conceive apparatus for human flight.

James Bell Pettigrew (1832-1908), a comparative anatomist from Scotland, has also added to our understanding of animal locomotion, especially in regard to the flight of insects, birds, and bats. As one can imagine, there was a rivalry with Marey, especially in regard to research on flight. After all was said and done, they both came to similar conclusions. Pettigrew’s Animal Locomotion, or, Walking, Swimming, and Flying, with a Dissertation on Aëronautics (London) was first published in 1873 and a three volume set Design In Nature (London, New York) was published posthumously in 1908- volume three is devoted to Animal Locomotion.

Zoologist Sir James Gray (1891-1975) spent over forty years studying animal locomotion and was influential in building a department of zoology at the University of Cambridge. He is also known for his pioneering work with cytology/study of cells (Text-book of Experimental Cytology, 1931) and as one of the founding editors of the Journal of Experimental Biology (1925-54). His 1951 Royal Institution’s Christmas Lectures were published in the book How Animals Move (Cambridge University Press, 1953) and his book Animal Locomotion (London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968) appeals to the biologist, but also to the physicist and the engineer.

Another important zoologist who has enriched our understanding of the mechanics of animal and human movement (also dinosaurs) is Robert McNeil Alexander (1934-). He is a prolific author and has published over 280 papers, as well as a variety of books such as Human Bones: A Scientific and Pictorial Investigation (New York, Pi, c2005), Principles of Animal Locomotion (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2003), Optima for Animals (Princeton, Princeton University Press, c1996), Exploring Biomechanics: Animals in Motion (New York, Scientific American Library, c1992), Dynamics of Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Giants (New York, Columbia University Press, c1989), Locomotion of Animals (Glasgow, Blackie, 1982), and Mechanics and Energetics of Animal Locomotion (London, Chapman and Hall, 1977).

Even though we have over 2,000 years of animal locomotion studies under our belt, there is still much to learn and discover about the movement of animals. Today’s researchers of locomotion are seeking an integrated approach that draws on various fields and specializations from the molecular to mechanical and from the physical to the mathematical. By applying highly-sophisticated mathematical and computational methods, we can better understand the movement of animals through water and air, which in turn can help improve vehicle designs. You can find an example of these studies in Animal Locomotion: The Physics of Flight-The Hydrodynamics of Swimming (Berlin, London, Springer, c2010). Researchers are also using animal locomotion studies in mechanical engineering and biomechanics (Borelli would be proud!). Many universities have laboratories that focus on biomimetic robotics and bio-inspired robots – check out the M.I.T. Biomimetic Robotics Lab and UC Berkeley Poly-Pedal Lab .

Comments

This is a wonderful survey of the literature and great peek into the comprehensive holdings of the Library of Congress. I vote with you on Lascaux (and other caves with prehistoric paintings of that type) as a good starting point. Very nice and many thanks!