The following guest post was written by Barbara Bair, curator of literature, culture and the arts in the Library’s Manuscript Division; Suzanne Schadl, chief of the Hispanic Division; Dani Thurber, reference librarian in the Hispanic Division; Melanie Zeck, reference librarian in the American Folklife Center; and John Fenn, head of research and programs in the American Folklife Center.

On February 6, the Library of Congress kicked off its winter/spring National Book Festival Presents season with ”Fearless: A Tribute to Irish American Women,” which featured a conversation among award-winning novelist Alice McDermott, Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon and CBS anchor Margaret Brennan. As part of the programming surrounding this event, staff from four Library divisions—Manuscript, Prints & Photographs, Hispanic, and the American Folklife Center—were asked to develop a display of items related to the event that would facilitate connections and engage the public with diverse collections at the Library of Congress.

Confronted with the challenge of selecting materials for this purpose, the display’s curators agreed on the best approach: they would uncover treasures within the Library’s collections that brought to life captivating examples of the impact of women of Irish heritage in the Americas.

In this post you’ll find citations and descriptions for some of the items highlighted in the display and the event itself. If you have a favorite item, let us know in the comments below!

Lucy Burns and Edna St. Vincent Millay

Among the “fearless” Irish American women the Manuscript Division and Prints & Photographs Division highlighted in their combined portion of the display were activists Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950)—recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923 for her collection “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver” (1922)—and Lucy Burns (1879-1966), who with her close friend Alice Paul founded the National Woman’s Party (NWP) in 1916.

Burns was born into a large Irish-Catholic family in Brooklyn, New York. Her activism reflects the strong triangle of influence between the militant wings of the woman suffrage movements in the United States, England and Ireland. While studying in Germany and at Oxford, Burns was inspired by the work of Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and the Irish Women’s Franchise League (IWFL). She met Paul as a fellow WSPU protester in London, and worked as a salaried organizer for the WSPU from 1910 to 1912.

After returning to America, Burns and Paul brought fresh energy and direct-action experience into the Congressional Committee of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). They organized a massive American women’s suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., in March 1913, in counterpoint to Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. After heading the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, in 1916 they founded the NWP, which in 1917 became the first political organization to picket the White House. Lucy Burns was arrested six times while protesting, and in the Fall of 1917, she, Paul and other activists engaged in hunger strikes and endured forced feedings while incarcerated as political prisoners in the District Jail or a nearby workhouse in Virginia. In a mass mailing in November 1917, Burns appealed to NWP members to contact President Wilson to protest the treatment of Paul and fellow hunger striker Rose Winslow and encouraged volunteers to come from around the country to join in the picketing campaign.

NWP actions were designed to gain media coverage, influence voters and sway public, presidential and congressional opinion, in order to obtain the right of American women to vote by means of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Irish women won the right to vote on a limited basis in February 1918, with further expansion of franchise rights in 1922. In the United States, the 19th Amendment was successfully passed in Congress in June 1919 and ratified by the states in August 1920. “Shall Not Be Denied,” an exhibition showing some of the rich collections of the Library of Congress on the history of women’s suffrage, is currently on view and available online.

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Irish roots trace back on her father’s side to 18th century Ireland. Like Burns before her, Millay studied at Vassar College. She gained admiration as much for her ethereal ginger-haired beauty and liberated New Woman life style as for her mastery of the sonnet form. She moved in avant-garde circles in Greenwich Village before establishing her Hudson River Valley country home, Steepletop, with husband Eugen Boissevain, whom she married in 1923. Their 75½ Bedford Street home, which served as a West Village salon near the Cherry Lane Theater, remains famous as the narrowest row-house in New York. American essayist, critic, and New Republic editor Edmund Wilson—who later married “Memories of a Catholic Girlhood” author Mary McCarthy—was a close friend. In a whimsical photograph (left), Millay, Boissevain and Wilson parody the “greening” gardening and environmental movement of the time by planting poems instead of flowers in their garden, complete with a scarecrow to watch over the poetry.

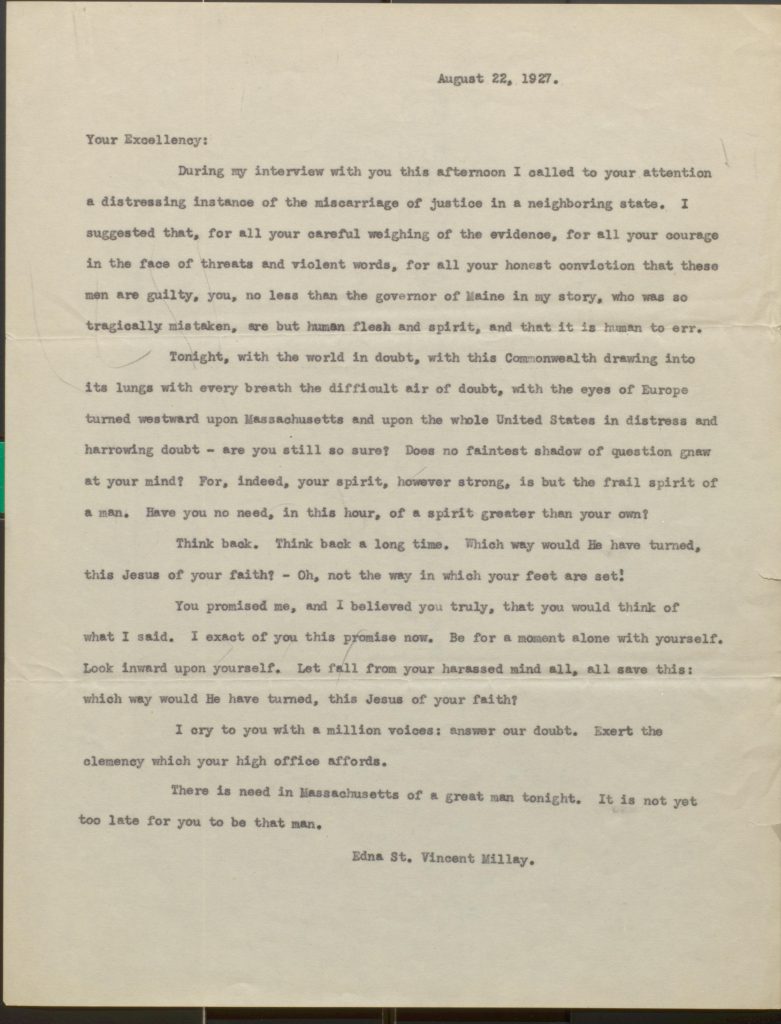

Not all was fun and games. Like Burns, Millay was no stranger to direct action and picketing for political causes. Famous for her meditations on kinds of love and her paeans to nature, Millay also addressed social justice in her poems. In 1927 she joined other progressive writers and public intellectuals like John Dos Passos, Dorothy Parker and Katherine Anne Porter in protesting the death penalty applied to Italian anarchist immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. Their 1921 murder trial took place in an atmosphere of anti-Italian, anti-Leftist and anti-immigrant popular sentiment that many felt prejudiced the outcome. The day before the August 23, 1927, executions took place, Millay reached out to Gov. Alvan T. Fuller to plead for clemency on the basis of reasonable doubt. She told him the eyes of the world were on Massachusetts. Her protest poem “Justice Denied in Massachusetts” was published soon after (“Evil does overwhelm / The larkspur and the corn; / We have seen them go under”).

In selecting their materials, the Hispanic Division was interested in helping diversify the focus of the collections display to include Irish immigrant women/families in Latin America.

Argentina welcomed the largest number of Irish immigrants outside of the English-speaking world, and the tragic story of Argentine-Irish woman Camila O’Gorman is worthy of note. O’Gorman (1828-1848) challenged Argentina’s government and the Catholic Church by pursing her love for Ladislao Gutiérrez, a young Jesuit priest from the local parish. They eloped and traveled north in hopes of leaving the country.

As Camila’s prominent Irish father wrote the dictator to blame Ladislao for seducing and kidnapping his daughter, others blamed Rosas for the moral corruption of women in Argentina, often scapegoating Irish parishioners. The lovers were captured, imprisoned and executed by firing squad when Camila was 20 years old and eight months pregnant.

- “Camila O’Gorman, o, El amor y el poder.” Leonor Calvera. Buenos Aires: Editorial Leviatán, 1986. https://lccn.loc.gov/bi89003234

- “Evita, Inevitably: Performing Argentina’s Female Icons Before and After Eva Perón.” Jean Graham-Jones. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2014. https://lccn.loc.gov/bi2016000172

- “Paisanos: The Irish and the Liberation of Latin America.” Tim Fanning. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018. https://lccn.loc.gov/2018022275

Did you know an Irish-born woman helped lead Paraguay in a war with Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay? Cork-born Eliza (or in Spanish Elisa) Lynch (1835-1886) fought for Paraguay in the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870) alongside her lover, Gen. Francisco Solano López. That war killed 50% of Paraguayan women and 90% of Paraguayan men—including López—but Lynch gained a lot of property in the process. This paradox led many to call Eliza Lynch the Lady Macbeth of Paraguay.

Lynch is memorialized in history, fiction, and film as these works demonstrate:

- “Shadows of Elisa Lynch: How a Nineteenth Century Irish Courtesan Became the Most Powerful Woman in Paraguay.” Sian Rees. London: Review, 2003. https://lccn.loc.gov/2003427147

- “Eliza Lynch, Regent of Paraguay.” Henry Lyon Young. London, Blond, 1966. https://lccn.loc.gov/66068117

- “Madame Lynch & Friend: A True Account of an Irish Adventuress and the Dictator of Paraguay, Who Destroyed that American Nation.” Alyn Brodsky. New York: Harper & Row, 1975. https://lccn.loc.gov/74015813

- “Empress of South America.” Nigel Cawthorne. London: Heinemann, 2003. https://lccn.loc.gov/2003430395

Lynch’s own “Exposición y protesta” contains letters written by her, her seven children and several members of the López family. As the late Joseph T. Criscenti (a contributing editor of the Handbook of Latin American Studies) noted, this printed collection is “very informative on Lynch’s efforts to secure possession of properties she acquired before 1870, and on controversy between Lynch and the López family over the estate left by Solano López.”

Mrs. Ben Scott and Maggie Hammons Parker

To celebrate “Fearless: A Tribute to Irish American Women,” the American Folklife Center curated its display to showcase the songs, instrumental renderings and stories of Irish American women. The Center’s contributions took two forms: a display of collection items for the public and a curated mix of field recordings for the presenters in the evening’s event.

The visual exhibit presented materials such as songsters, fliers, programs, images, handwritten field notes and interview transcripts demonstrating the range of items that the Center holds related to Irish American cultural heritage. Each of the display items related (directly or indirectly) to the musical compilation given to Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon, Alice McDermott and Margaret Brennan, a mix of field recordings replete with well-known tunes—such as “Ireland’s Green Shore”—alongside lesser-known gems, such as “Put Your Little Foot Right There.” Collectively these visual and sonic selections represented 130 years of Irish American history from communities across the country.

|

|

1973. American Folklife Center. |

Within the visual exhibit, the Center paired documentation connected to two musical recordings from its collections: a fiddle version of “Irish Washerwoman” (as played by Mrs. Ben Scott in California and recorded by Sidney Robertson in 1939), and the unaccompanied ballad “Ireland’s Green Shore,” sung by Maggie Hammons Parker in West Virginia and recorded by Alan Jabbour in 1970. This ballad appeared in the on-stage program Thursday night and was also included in the special gift given to three participants.

To different degrees, both songs—either through the title or the lyrics—make a direct reference to Irish culture or Ireland. However, the textual materials accompanying these songs—a dust jacket with Robertson’s handwritten notes about Scott and a segment from Parker’s conversation with Center staff folklorist, Carl Fleischhauer—offer insights into the intergenerational transmission of culture heritage within the familial settings. For example:

Carl to Maggie: Some of the songs you learned from an uncle, or your father?

Maggie: Yes—there was a lot of ‘em I learnt from him. He was pretty bad to sing.

Carl: Your dad?

Maggie: Yessir… He’d tend to the children…

Carl: Did you learn those from your cousin?

Maggie: Huh? Yes, some of ‘em I did. And then I had another cousin. … that’s the way I got part of the songs.

—from the liner notes to an audio compilation released by the American Folklife Center, “The Hammons Family: A Study of a West Virginia Family’s Traditions“

Similarly, Robertson comments on the dust jacket of the “Irish Washerwoman” recording that “Mrs. Ben Scott learned to fiddle as a child in Monterey, C. She cannot read notes.” Her position as the folklorist/ethnographer is similar to that held by Jabbour and Fleischhauer during their multiple visits to the Hammons family, but the conversational interaction between Fleischhauer and Parker allows for Parker’s perspective to surface as a valuable source of information—on its own and in conjunction with the music.

Comments (2)

Question: Is it true that in 1900 the American ethnic group with the most young women pursuing post-high school education (in colleges and universities) were Irish-Americans?

Dear Maureen,

I’ve added your question into our Ask a Librarian system. A reference librarian will be in touch with you soon with a more complete response.

All best,

Anne

Comments are closed.