Cartographic depictions of Seoul, the present-day capital of South Korea, during the time of the Japanese occupation of Korea are not often seen and the surviving artifacts a bit rare. The period of Japanese influence and control over Korea lasted from 1905 until 1945. It began with a protectorate that escalated into a full-scale colony and ended with the Allied victory over Japan in World War II. During the period of Japanese rule, the name Seoul was not used by the Japanese as a place name; instead, it was called Keijo in Japanese or Gyeongseong in Korean.

As part of its efforts to carve out its authority on the Korean peninsula, the imperial Japanese administration renamed local landmarks and geographic locales, reflecting those name changes in new maps. In 1910, the Japanese published the map of Seoul, seen below, annotated in English with red ink, to depict the important Japanese governor’s residence, as well as military and police installations, consulates, hotels, banks, museums, and gardens, among other locations. In the upper, middle portion of the map sits Gyeongbokgung Palace, which is annotated as “Keifuku Palace.” To the west of the palace is Seodaemun Prison, which was used to hold political prisoners. In the south is the city’s main rail hub, ”Nantaimun Station” (Namdaemun means “Great South Gate” in Korean), which was renamed Seoul Station in 1947.

While the Japanese occupation of Korea was frequently brutal, with most political dissent and expressions of Korean culture harshly suppressed, the Japanese projection of their position in Korea softened considerably when shared with the West. In 1913, the Japanese Tourist Bureau published a two-sided map that promoted Seoul to potential American and European tourists. The map, with its warm and inviting colors, lists sight-seeing destinations. Prominently illustrated is the extensive stone wall that once guarded the ancient city. On the reverse side, the brochure states: “Tourists, who have enjoyed their excursions in the charming ‘Land of the Rising Sun,’ should come over to Chosen (Korea) and stay in Keijo to see the quaint attire and observe the peculiar customs and distinctive architecture of the ‘Land of the Morning Calm.'” A regional map, to the left of the text, depicts the proximity of Korea to Japan and a number of routes one could take by ship to visit. Speaking to Japan’s imperial authority over Korea, the brochure informed foreign visitors who enter Korea by way of Japan that “passports are now abolished” and baggage will be examined by Japanese and local customs officials.

A decade later, the Japanese Tourist Bureau continued to market Seoul to Western tourists. The cover of a brochure, seen below, illustrates a woman in traditional dress gazing upon Gyeongbokgung Palace, perhaps an artist’s attempt to convey a romantic notion of a people and way of life unblemished by industrialization. The city map is semi-ringed with photographs, with the first illustrating the modern Chosen Hotel, which offered comfort and amenities that appealed to Western travelers, and the remainder of the photographs showing traditional depictions of Korean life and architecture that one might encounter on a sightseeing excursion. Tying the message together is the pink background, a color that symbolizes trust in Korean culture. Note the figures outlined in white wearing traditional dress and partaking in everyday life. On the reverse is a lengthy text explaining the geographic position of the city; a guide to banks, hotels, restaurants, and consulates; and suggested plans for sight-seeing excursions. Nearby destinations are highlighted, such as a trip to a hot spring.

Note: We clarified that Seoul Station was called originally called Namdaemun Station.

Comments (4)

Thank you for posting these old maps. Seoul Station used to be called the Namdaemun or South Gate Station. There was an earlier station a few blocks north. Gradually over time, the Namdaemun station became known as the Seoul Station.

And the station Fred mentioned is still there. There are still some post-liberation questions remaining in Seoul, namely the appropriateness of iconoclasm in terms of the Japanese occupation of Korea. These buildings, constructed with the blood, sweat and tears of the Korean people, were products of the Japanese architect’s imagination built in service of the Japanese. The old Shinsegae department store building was originally the local franchise of the Mitsukoshi department store chain.

Re:A List of Potential Targets in Seoul

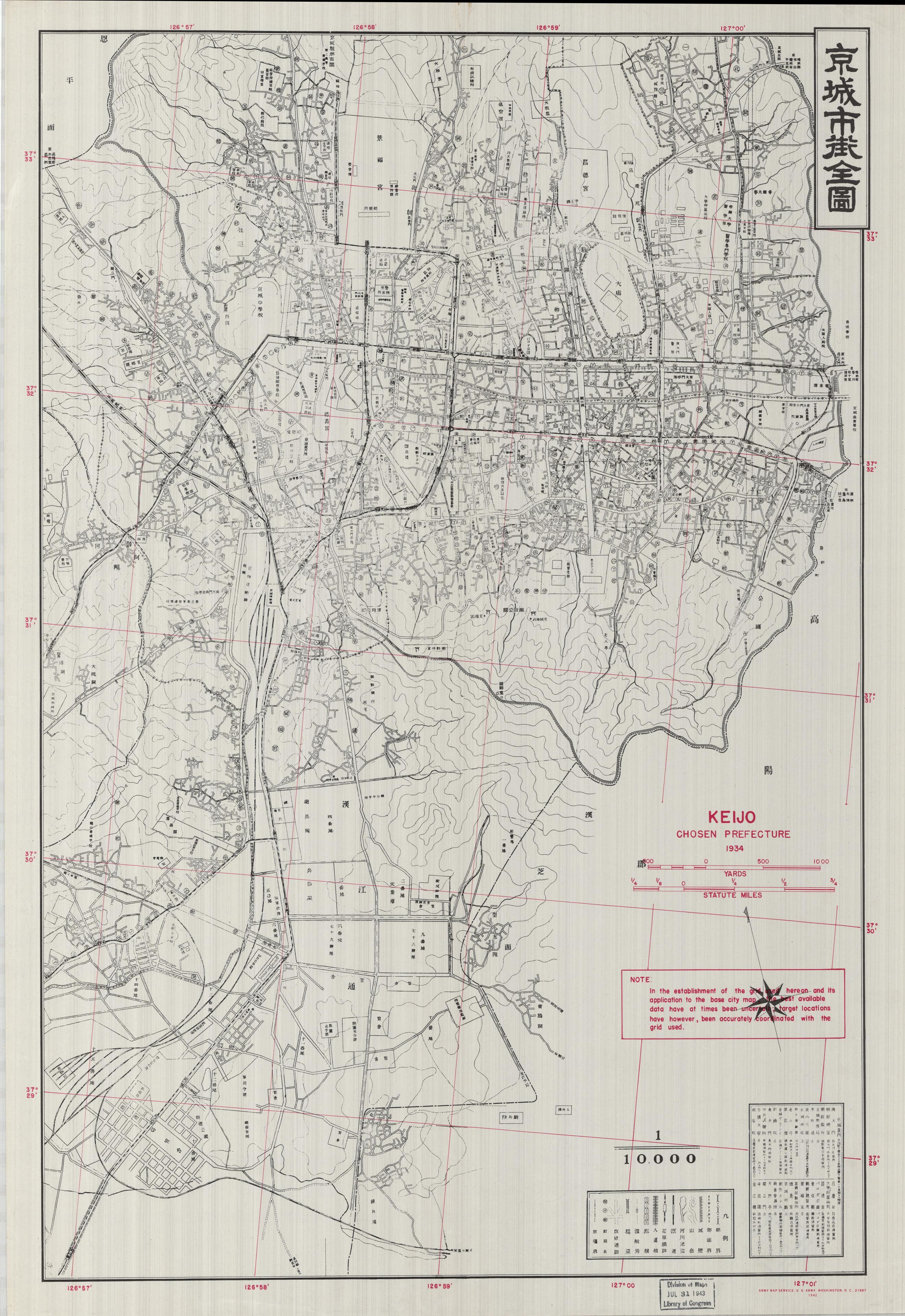

Keijo, Chosen Prefecture, 1934.

Where do you think I can get the list of potential

target in Seoul?

What would be the 38th Parallel in the datum used on Japanese, Soviet maps of Korea just prior to the Korean War? What datum was used at that time to show 38th Paralell border posts?